CLICK HERE TO REGISTER FOR THIS COURSE

- Target Audience: Mental Health Professionals

- Live, Interactive Webinar Continuing Education Hours: 10 (Ten)

- Day One: Tuesday, February 27, 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. PST

- Day Two: Wednesday, February 28, 10 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. PST

Course Description

This is a TWO-DAY seminar consisting of TWO days of five-hour live, interactive webinars. You must be present for BOTH days to get credit for the course.

Please note that course times above are Pacific Standard Time.

Ecopsychology is the study of how the natural world impacts mental well-being. Ecotherapy is the therapeutic application of this knowledge. This live, interactive webinar course will introduce you to some of the basic skills, techniques and research in the field. The course also covers some of the latest research in ecotherapy, practice with some common ecotherapy interventions, and studies that used ecotherapy to treat anxiety and trauma.

WEBINAR Ecotherapy for Therapists Course Information Packet

Course Objectives

After successfully completing this course the student will be able to:

-

- Discuss and describe the concept of Ecopsychology

- Discuss and describe the concept of Ecotherapy

- Discuss some of the characteristics of the Green Care model

- Describe a rationale for the use of ecotherapy in therapeutic settings

- Discuss the roots of ecotherapy in indigenous shamanism

- Discuss Nature Deficit Disorder as proposed in the book, Last Child in the Woods by Louv

- Describe some of the research into Nature as Nurture

- Discuss some research in Nature and Child Development

- Discuss the Eco-Educative Model proposed by Pedretti-Burls (2007)

- Discuss how ecotherapy facilitates mindful states

- Discuss ecotherapy for treating addiction

- Discuss ecotherapy for treating trauma

- Describe and discuss some ethical issues of ecotherapy

- Name some colleges that offer ecotherapy programs

- Discuss some future directions for ecotherapy

Click here to read our Privacy Policy, Terms and Conditions, and Program Policies

Courses are best viewed using Firefox, Safari, Chrome, or Internet Explorer. Other browsers may create login issues. If you are having difficulty logging in, please switch to one of these browsers or empty your browser’s cache.

Instructor Qualifications and Contact Information

This course was created by Charlton Hall, MMFT, PhD.

Charlton Hall, MMFT, PhD is a former Marriage and Family Therapy Supervisor and a former Registered Play Therapy Supervisor (now retired from both those roles).

In 2008 he was awarded a two-year post-graduate fellowship through the Westgate Training and Consultation Network to study mindfulness and ecotherapy. His chosen specialty demographic at that time was Borderline Personality Disorder.

Dr. Hall has been providing training seminars on mindfulness and ecotherapy since 2007 when he founded what would become the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, LLC, and has been an advocate for education in ecotherapy and mindfulness throughout his professional career, serving on the South Carolina Association for Marriage and Family Therapy’s Board of Directors as Chair of Continuing Education from 2012 to 2014.

He served as the Chair of Behavioral Health for ReGenesis Health Care from 2014 to 2016 and trained all the medical staff in suicide risk assessment and prevention during his employment at that agency.

Dr. Hall is also a trained SMART Recovery Facilitator and served as a Volunteer Advisor in South Carolina for several years.

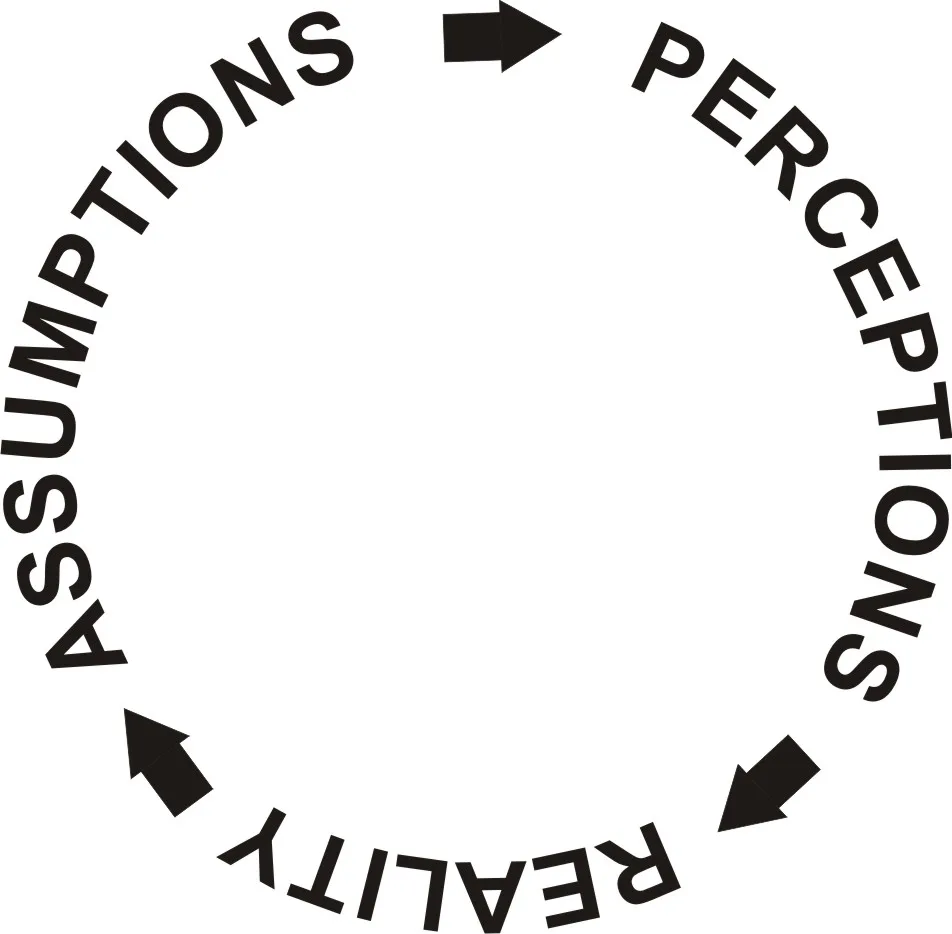

Dr. Hall’s area of research and interest is using Mindfulness and Ecotherapy to facilitate acceptance and change strategies within a family systemic framework, and he has presented research at several conferences and seminars on this and other topics.

Click here for instructor contact information

Click here to see a biography and summary of credentials for the Instructor

DISCLAIMER

The Mindful Ecotherapy Center, LLC has been approved by NBCC as an Approved Continuing Education Provider, ACEP No. 7022. Programs that do not qualify for NBCC credit are clearly identified. The Mindful Ecotherapy Center, LLC is solely responsible for all aspects of the programs.

All course materials for this online home study continuing education course are evidence-based, with clearly defined learning objectives, references and citations, and post-course evaluations. Upon request a copy of this information and a course description containing objectives, course description, references and citations will be given to you for your local licensing board.

All of our courses and webinars contain course objectives, references, and citations as a part of the course materials; however, it is your responsibility to check with your local licensure board for suitability for continuing education credit.

No warranty is expressed or implied as to approval or suitability for continuing education credit regarding jurisdictions outside of the United States or its territories.

If a participant or potential participant would like to express a concern about his/her experience with the Mindful Ecotherapy Center, NBCC ACEP #7022, he/she may call or e-mail at (864) 384-2388 or chuck@mindfulecotherapy.com. Emails generally get faster responses.

You may also use the contact form below.

Although we do not guarantee a particular outcome, the individual can expect us to consider the complaint, make any necessary decisions and respond within 24 to 48 hours.

Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Refund and Return Policy

Be informed when new courses are added –

subscribe to the Mindful Ecotherapy Center’s monthly newsletter.

Contact MEC | Help with Courses | My Account | Student Forum